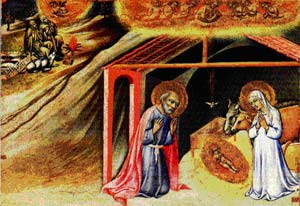

However later depictions simply show the adoration with the various elements described in the vision, for example a small panel of the Nativity by the Sienese painter, Sano di Pietro, painted around 1445 and now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana.

The influence of both the Meditations and the Revelations of St. Birgitta can be seen in the Portinari altarpiece, painted in Bruges by Hugo van der Goes for the Florentine merchant, Tommaso Portinari and then shipped to Florence and displayed on the high altar of the Portinari church, S. Egidio.

The naked child lies, cold and vulnerable on the bare ground, as described in the texts. The Virgin kneels before him. Uncouth shepherds, the first to recognize him, stumble in at the background. The pillar mentioned in the Meditations is seen beside the manger. The angels wear vestments suitable for the celebration of Mass, and the Eucharistic significance of the wheat, placed directly under the infant body of Christ, is clear.

The painting was very influential in Florence. Although Netherlandish painting was imported to Florence throughout the fifteenth century, nothing of this scale (the altarpiece is very large, taking up the better part of a wall of the Uffizi) had been seen before. Soon artists began to copy the exquisite wintry, northern landscape found in the altarpiece, with its winding hills and rivers of a type never actually seen in the Netherlands. An early tribute was Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Nativity painted for the Sassetti chapel in Santa Trinita, Florence, for the Florentine merchant Francesco Sassetti.

Ghirlandaio takes some elements, such as the shepherds grouping, but Italianizes them. The shepherds are no longer the uncouth peasants of the Van der Goes piece, but refined Italian humanists. The manger is now a classical sarcophagus, the stable now supported on classical piers, and the naked child is no longer thin and vulnerable, ready for the sacrifice of the Mass, on a bare piece of ground, but a chubby child protected from the ground by lying on the edge of his mother’s cloak. The saddle, mentioned in the Meditationes can be seen behind the Virgin, and in the background, the Magi process through a triumphal arch.

The kind of homely detail described in texts such as the Meditations, the Golden Legend and Birgitta’s Revelations are depicted more enthusiastically in northern European painting than in Italian.

This painting includes the somewhat quaint detail of Saint Joseph mending his hose while the Virgin looks on. Everyday domestic crockery is seen on a low table in the foreground, while in the background a nimbed figure places the Christ Child in the manger, watched by the ox and the ass. The nimbed figure may be the good midwife, or one of the Virgin’s handmaidens, or even perhaps Saint Birgitta, although her bare head and youthful appearance make this last possibility somewhat unlikely. She may also be Saint Anastasia, who was rewarded for her piety by being allowed to hold the Christ Child in her vision of the nativity.

Saint Joseph’s role here may have more symbolic significance. In Middle Dutch and Germany folklore, Saint Joseph was believed to have made Christ’s clothes out of his stockings, and relics of his stockings were kept in Aachen Cathedral. However, the homely nature of Saint Joseph can hardly be denied and this is in keeping with northern tradition, which often saw Joseph as a cuckolded, comical figure. In this panel by Konrad von Soest Saint Joseph, smaller scale as usual, is shown blowing on food:

While a French panel, now in the Bargello in Florence, shows Saint Joseph washing his feet while the Magi present their gifts.

However, a charming panel from c.1410, now in Berlin, presents Saint Joseph as a more serious paterfamilias, working at his carpentry while the child Jesus runs to him and angels help roof the shelter of the family; one even climbs a ladder instead of using the more obvious method of flying.

The Gospel of Luke says that Jesus was circumcised a week later and named (Luke 2:21-22). The purification scene in the Arena chapel follows scripture closely.

The time then came for Joseph and Mary to perform the ceremony of purification as the Law of Moses commanded. So they took the child to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord, as it is written in the law of the Lord: “Every first-born male is to be dedicated to the Lord.” They also went to offer a sacrifice of a pair of doves or two young pigeons, as required by the law of the Lord.’ Luke goes on to tell us that there was an old man named Simeon who had been promised by the Lord that he would see the saviour of Israel. Simeon took the child in his arms and foresees not only the death of Christ, but the grief of Mary: ‘ And sorrow, like a sharp sword, will break your own heart.’ Anna, the daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Asher, a widow who never left the temple, arrives and gives thanks for the child (Luke, 2:22-38; Matthew 2:1-12). The circumcision, omitted in the Protevangelium, is recounted in the Pseudo-Matthew before the Adoration of the Magi. On the sixth day, the family enters Bethlehem, where they spend the week. On the eighth day, with the circumcision, the baby is given the name Jesus, as he was called by the angel before he was conceived in the womb. This is shown by Giotto not in one of the main narrative scenes in the Arena Chapel, but in a small quatrefoil on the decorative bands. Despite the low key nature of the representation, it an important scene, as it shows the first shedding of the blood of Christ, and as such, was considered a type of the Passion.